“Honestly, we weren’t sure that those kinds of products would have any success, that’s why we were late.”

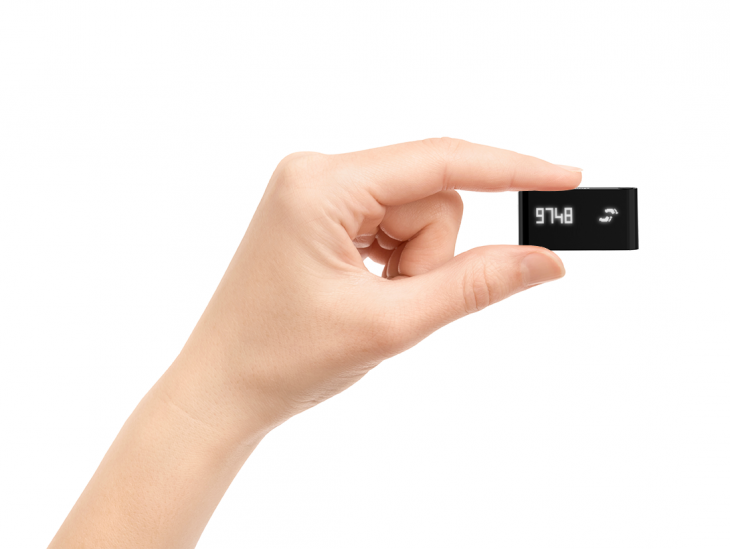

Alexis Arquilliere of Withings is explaining why the company, known for its line of connected health products like blood pressure monitors and scales, took so long to develop its own personal monitoring device. The unit, called the Smart Activity Tracker, is a unit the thickness of a chocolate holiday wafer and half the length of a stick of gum.

It’s also relatively late to the party. The similarly sized Fitbit is already a mild hit and there are contenders around every bend, including the Fitbug, also announced at CES, as well as the Nike Fuelband and the Jawbone UP.

And it’s also following on with a larger trend, that of monitoring your body, your surroundings and your possessions, and funneling that data through your pocket computers. Two ‘next big thing’ trends are at work here: Quantified Self and the Internet of things.

Quantified Self, a concept that has been around since the 70’s in various forms, is the practice of monitoring your body to gather data. You log its activity, its inputs (food) and outputs (energy) to provide yourself with a ‘quantifiable’ picture of your actions. In recent years an explosion of monitoring devices and software solutions has pushed this from a research field into an area of consumer interest.

The Withings Smart Activity Tracker is one of those, as is the new version of its connected scale, the Smart Body Analyzer. Both the scale and the tracker have added heart-rate monitoring, something that puts their products just a bit above the rest of the pack like Fitbit.

To monitor your heart rate, you hold your finger against the side of the tracker for 5 seconds or so. You’re then presented with a pleasant animation and your current rate. Do this often enough and the rate becomes a part of your overall rating in the Withings app for smartphones and the web. You can then visit the app to see things like your Weight (provided you’ve entered it manually or via the scale) steps, heart rate, sleep duration and more.

“We didn’t think that there being competitors was any reason for us not to enter the market,” Arquilliere adds. He says that Withings felt that it could bring more to the table in the Quantified Self arena, including the heart rate monitoring and the new scale’s air quality measurements. “People spend most of the time at home in the bedroom,” he adds, “so that’s where we recommend you put the scale.”

Having it there will encourage daily use, as well as logging of your air quality (to see if elevated CO2 levels are present) and heart rate through the soles of your feet.

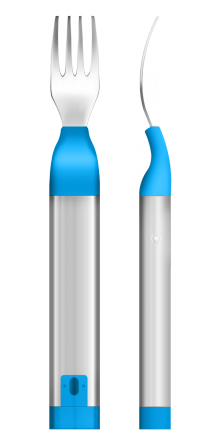

This fascination with logging was also displayed in the HAPILABS HAPIfork. Yes, it’s an electronic fork that logs your meals, time between bites and even warns you when you’re not giving yourself enough time to chew. If this sounds relatively Orwellian, you’d not be far off.

But products like the HAPIfork and the Withings Smart Activity Tracker are aimed squarely at the market of people who are fine with the idea of these data sets being exposed. People who don’t mind seeing, in what are at least close to hard facts, exactly how the human machine that they inhabit is performing.

This ties into the concept of ‘sousveillance‘, a predecessor to the Quantified Self movement. Essentially the monitoring of a situation by a participant, rather than an outside third-party. Once a scientific niche, the explosion of Internet connected devices like smartphones has made it a reality. Nearly all are inhabited by social networking apps that voraciously consume our data and turn it into money via advertisements. Even if you’re not a participant, anonymized data is being gathered about your activity to improve cellular service and wireless technologies by the manufacturers.

If these companies are gathering your data, why shouldn’t you do the same? Not all of us may want to be data scientists, and not all of us need to use devices like this to make us aware of our physicality. But if you are interested, then there are now more options than ever, and those expand outwards from the body to include the environment around it.

The Neatatmo Personal Weather Station is a two-component product that allows you to monitor atmospheric conditions both inside and outside your home. It connects to your phones, tablets and the web to allow you to gather data about the environment where you are now, rather than where a weather station is.

“In Paris, where I live,” says Neatatmo Product Manager Romain Paoli, “the weather station is on top of the Eiffel Tower. That doesn’t give me an accurate reading of what the weather is like at my front door.”

While weather may seem like a niche market, Paoli says that the need for a product like Neatatmo goes beyond the just weather nuts. In fact, the larger interior sensor is the one which he says provides a benefit to anyone, regardless of their weather obsession. It monitors oxygen levels in the home, can detect high amounts of CO2, humidity, temperature, noise pollution and more to give you an idea of how healthy and comfortable your home actually is.

High amounts of noise, for instance, wont kill you, but they will affect your ability to concentrate, an important factor for home workers.

Neatatmo, somewhat unsurprisingly, has as its CEO the co-founder of Withings, Fred Potter. The product philosophy of the two companies is somewhat similar, even if the products differ in features. The Neatatmo is simple and attractive, with a feature-rich but easy to use monitoring app. The Withings baby monitor shows some inklings of what the Neatatmo does as well, monitoring humidity and temperature in your baby’s room.

But the benefits of the Neatatmo, says Paoli, go beyond just personal monitoring. You’re also able to contribute back to the world at large with data about your own personal microclimate. The Urban Weather project aims to be the “largest community based weather and Air Quality monitoring network ever established.”

By gathering data from Neatatmo units locally, the company hopes to be able to provide a better, more accurate picture of weather in urban areas. Hundreds or thousands of unique data points rather than one or two centralized monitoring systems can map out the weather not just of a region, but also of a city or a street. The possibilities here are intriguing.

Spiraling further outwards from your body, a new product from automotive parts manufacturer Delphi adds your car to the Internet of Things. If you’re not familiar with the concept, it started out as a system for using RFID to monitor inventory like food or perishables and has expanded to include many objects that can be connected and tracked via the Internet via a variety of technologies.

In Delphi’s case, the device they’re connecting to the internet is your car.

Most vehicle companies are investing in modern cloud-connected systems for their cars, and the industry estimates are that all new cars will be connected by 2016. But that, says Delphi’s Advanced Concepts Manager Craig Tieman, leaves out the millions of used vehicles that will never get the advantages of these new technologies.

That’s where the Delphi Connected Car comes in. Essentially a dongle that plugs into a standard car diagnostic port (your car has one if it’s newer than 1996) and monitors information coming off of the vehicle’s onboard computer. This includes tracking, trip times, vehicle status, engine fault codes and more.

There are companion apps for Android and iOS that allow you to tap into the information that would typically only be seen by a technician or not at all.

One of the marquee features of the app is the ability to mimic your keyfob functions. The fancy keys that you get from the dealer nowadays use radio frequencies to talk to your car to do things like unlock it, remote start it etc. The Delphi dongle and app, after a short setup process, duplicate those things entirely. This means that if your smartphone is in hand, you can use it as your key rather than your actual key. Password protection is available obviously and the communications are encrypted end-to-end with 128-bit AES.

But the keyfob emulation isn’t the slickest part. Because the dongle is provided power by the car, you can also use the app as a locator to find it (through Delphi’s cloud) without ever having to ‘drop a pin’ to remember where it is. You can also set alerts for speed or travel using geofences. This means that you can tell when your car leaves your home, alerting you to theft, and you’ll know when it arrives at a destination.

Tiernan gives the example of a friend whose daughter was driving to a friend’s house in the snow at night. “They were able to track her all the way there, to see that she got there safely,” he says.

Obviously, the possibilities for tracking could extend to seeing where your kids are going and that raises a whole set of parental privacy issues, but that’s up to the user to decide, says Tiernan, as the tracking is opt-in.

Automatic trip logging with export options for expense reports and (in an upcoming version) breadcrumbs for more accurate routing information round out the options. It’s a one-stop shop for connecting your car and collecting all of the data you could ever want about it. The Delphi unit is launching soon in Verizon stores as part of a partnership, and the pricing hasn’t been announced, but as a car nut, this seems like a no-brainer to me.

What is it good for?

The products that we’ve seen at CES so far this year that allow users to collect data about themselves, their property and their environment are just the tip of the iceberg. This is a growing market and the methods will get more sophisticated and more accurate.

The question then becomes: why? Why gather all of this data about yourself and your things? We’ve been getting along for hundreds of years without really personally understanding these data sets, so why should we need to start now?

For me, it’s a matter of transparency and awareness. I’ve been testing several units including the Nike Fuelband and the LarkLife bracelet, and the biggest thing that it brings for me is a conscious knowledge of the way that I’m living. The data was always there, and there is definitely enough direct visual evidence that I’m not exercising as much as I should be, but the readouts of these devices give me hard data, a visual reference and goals to work for. As we become increasingly busy, offloading the tracking of things like our health or environment from the wetware computers of our brains to our portable devices doesn’t sound like such a bad idea at all.

In the end, we probably won’t have a choice. There will eventually be a time where almost any semi-complex product will be connected to the Internet or to our personal devices in some way.

The only question will be whether you tap into that collected data or not.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.